Marketplaces: The Common Questions VCs Will Ask

Written by Hunter Watkin, originally published on Medium

As a Seed investor, it’s my job to find the magic in early-stage marketplace startups, often before founding teams have written a line of code.

A software marketplace allows people who want a thing and people who can supply a thing, to transact efficiently and on the best possible terms. Hugh Williams describes it as matching supply and demand in a ‘democratic’ way.

It takes time to build software that meaningfully aids both supply and demand, so initially, startups must be crafty to attract users and get a marketplace off the ground.

To do so, you will almost certainly need some early capital. That’s where first believers like Rampersand come in.

While we don’t need to see a certain revenue figure or customer number before investing, we do need to believe that for a given market, a software marketplace can reduce friction for participants to such an extent that it becomes a total pain to transact anywhere else.

When you interact with Rampersand or another venture investor, you can expect questions on:

the extent to which supply is differentiated (ie heterogeneous vs homogeneous);

the steps required for parties to transact and how costs will be reduced;

whether the marketplace will be a geographical, category, or global winner;

the extent to which there is fragmentation of supply; and

where market inefficiency and under-utilisation exists.

Here’s the detail on why 👇

Q: To what extent is supply homogenous (or heterogeneous)?

The depth and variety of the products or services that sellers offer and buyers seek will dictate the discovery experience you build for customers.

Supply is homogeneous where it is functionally the same, regardless of who the supplier is. An example of homogenous supply is the secondhand tickets sold on the Australian-born marketplace, Tixel. General admission tickets sold for a given event all have the same function, no matter the seller. Buyers and sellers are not concerned with who the counterparty is, so long as tickets are available, as cheap as possible, and not fake.

This can be contrasted with the search experience required for Rampersand-backed, Expert360. Before Expert360, finding and engaging the right experts in a timely manner came at a huge discovery and transaction cost. Expert360 reduces this friction for businesses by aggregating and carefully vetting expert supply (i.e. Expert360 only allows ~10% of consulting applicants to list their services via its marketplace). It removes friction in searching and comparing supplier history and experience for firms that do not have the capacity to do the work themselves. For heterogeneous marketplaces, the core value is more about finding the best match rather than getting something as quickly and cheaply as possible.

The distinction between homogenous and heterogeneous supply also has implications for whether adding more supply reduces search costs for buyers. For homogenous marketplaces, if there are too many choices for buyers and insufficient means to compare them, this can result in decision fatigue and limit all-important conversion.

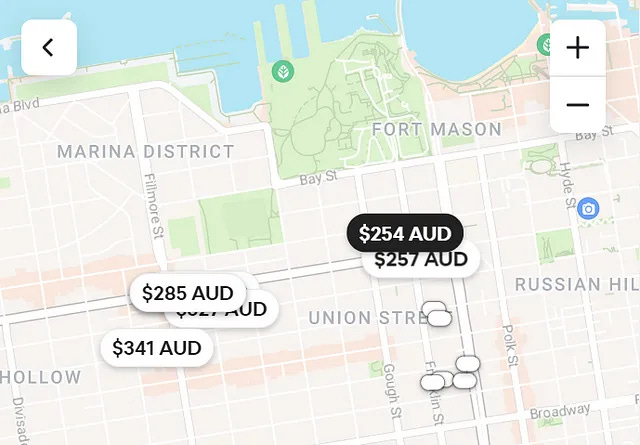

In the case of an almost perfectly heterogeneous marketplace like Airbnb, there is an argument that extra supply will never hurt the accommodation seeker’s experience, so long as the way properties are presented is well-optimised. For example, when you search for properties in a certain area with certain criteria on Airbnb, those that have a limited history or less suitably fit your search criteria are not presented as prominently (ie the smaller rounded rectangles).

An Airbnb search for a 1-night stay in San Francisco

Articulating how incremental supply will impact a marketplace has implications for how marketplaces scale, their market size, and how they take and keep market share long-term. Check out A16zs blog on how a disproportionate amount of supply or demand can pollute a marketplace experience here.

Q: What costs are you reducing for participants?

The extent to which marketplaces can add value to the ease and efficiency of a transaction dictates the all-important ‘take rate’ (a.k.a. transaction fee) a marketplace can charge parties. If your take rate is too high relative to the value you’re delivering, parties will do what they can to ensure marketplaces ‘take’ nothing at all by transacting offline.

Dan Hockenmaier divides the cost savings a marketplace can deliver into search, information and price discovery, policing, and security. It’s crucial that you explain which of these costs you will save and how it materially improves the status quo.

This is a plot by Dan Hockenmaier of how marketplaces charge transaction fees relative to their value-add.

For peer-to-peer (P2P) transactions between strangers, a key hurdle is having mechanisms that help police a transaction, by building trust and reliability. The best P2P marketplaces have been able to build this uniquely, but it has often required shifting consumer behaviour (i.e., getting comfort with strangers giving you lifts and inviting you for sleepovers in their homes). In the early days, it was very difficult for the marketplace to offer insurance to parties, so mitigating bad behaviour with the right vetting and incentive systems is crucial. As markets mature, insurance can be offered as either a loss leader or in Airbnb’s case, an upsell (i.e., Airbnb’s host liability insurance).

A business-to-consumer (B2C) transaction tends to provide a simple search and “buy now” experience with take-it-or-leave-it terms (i.e., buying clothes from the Iconic). The buyer gets the value of aggregated supply, payment, and delivery reliability, but the take rate is somewhat constrained as it has the option of transacting directly with retailers via their websites.

By contrast, a business-to-business (B2B) transaction almost always has more strings attached. These transactions usually have workflows that aid communication, aspects of procurement and negotiation, and in some cases provide the operating system for buyers/sellers.

RangeMe, an ANZ-born B2B marketplace connecting wholesalers and retailers, aids the buying journey by allowing wholesalers to list and manage inventory as well as empowering them to track, communicate with, and establish custom terms with interested retailers. This high single-player mode value is part of what makes the risks of transactions taking place ‘offline’ lower for managed B2B marketplaces.

Q: Will you win in a geography, a category, or globally?

Ultimately, the extent to which marketplaces ‘win’ falls into a few categories:

Global winners. These are rare. Horizontal marketplaces like Amazon Business and Alibaba are probably the closest examples of this. Peer-to-peer marketplaces like Airbnb and Uber have also been able to spawn internationally through customer travel.

Winner-takes-all markets (in a geographic/locational sense). Realestate.com.au and Seek are local examples of geographic winners, and this is repeatedly seen in areas like car-sharing and grocery delivery apps. These are often labelled ‘root-density’ markets in the sense that market dominance in one location makes you hard to displace, but does not necessarily guarantee success in a new location with earlier movers (ie Uber has won food delivery in Australia, but was humbled by DoorDash in the US).

There are then markets that can have multiple winners across categories with slightly different propositions globally. An example is holiday accommodation where the likes Expedia, Tripadvisor, Vrbo, Booking.com and more all have some but not dominant market share due to slightly different offerings.

In some instances, a plan to become one of several in a geography or a category can still be a huge business and attract venture funding (see my colleague Abhi’s article on what makes a business ‘venture scale’). How you articulate your understanding of an existing or emerging competitor mix in a category and location will be crucial to convincing an investor that you’re well-positioned to resource and make good decisions with funding.

Q: How fragmented is supply?

The extent to which it is hard to compare supplier options will impact the long-term value of a marketplace.

Before Airbnb, it was impossible to view all the private residences for which hosts were prepared to have guests stay in a certain geography. Supply was not just impossible to discover, but also highly fragmented. It has meant that as Airbnb has matured, even if you are visiting the same area, you still need it to see what’s available each time you travel.

By contrast, when you are working out how to travel to new places, it’s painful but not impossible to work out how to get around by researching independent travel providers. Hugh Williams reflected that in his time working with Trainline and Rome2Rio, he was blown away by just how complex it could be when it came to navigating parts of the UK and EU by train (in the case of Trainline) or by a combination of air, land, and sea (Rome2Rio).

These travel aggregators were able to solve a significant consumer coordination problem, but once a consumer knew their best routes, they retained the power to book this independently with a trusted brand (compared to a stranger in the case of Airbnb) albeit less efficiently. The available number of credible suppliers is also much lower than in the case of Airbnb.

Therefore, these aggregators only charge supply a modest fee for providing leads (typically less than 10%) and charge consumers nothing. Here lies the difference in take rates that an aggregator (which charges a fee for lead generation) can charge compared to a marketplace (which reduces so many costs that it wins the right to process the payment).

Supply fragmentation has huge implications for how acute the transaction inefficiency is and the unit economics of the marketplace. More on measuring fragmentation in a future blog.

Q: Is the supply under-utilised or inefficiently accessed?

What does Airbnb, Car Next Door, and local success story, Camplify, have in common? They allow ordinary people to make money from something they already own at (almost) no extra cost. You’ll hear this described by marketplace professors as unlocking an ‘underutilised fixed asset’, courtesy of Kevin Kwok’s seminal article.

Helen Souness, Rampersand Venture Partner, reflected that before Camplify, people would buy depreciating RVs and campervans that they would use for less than 80% of the year. Camplify allowed them to rent these assets out when not in use. For the demand side, holiday-seekers were now presented with a better-priced alternative to booking expensive holiday accommodation, camping in a tent, or having to buy an asset they would rarely use relative to its cost.

The lower the variable cost of delivering a product or service, the better, but it need not be zero. You might just offer a more attractive way of delivering/receiving a service. An example of this is Visory, which offers enterprise-grade bookkeeping services to SMEs and startups at an attractive price, while giving bookkeepers the opportunity to do more work, on more flexible terms.

Articulating your category (even if it is new), how your marketplace improves over time, and research or experience-based hypotheses for what will determine success will help communicate the magic of your marketplace and how emphatically it improves the status quo.

In future articles, I will dive deeper into how great marketplaces got off the ground and the metrics that matter to demonstrating marketplace progress.

If you’d like to chat further about this article or how Rampersand thinks about marketplaces, get in touch. My email is hunter@rampersand.com.